Comprehensive Management of Dizziness in Elderly Clients

Sandra M. Nettina, MSN, RN, CS, ANP

© 2001 Medscape, Inc.]

Abstract

Dizziness is a symptom experienced by one

quarter to one third of older adults. Etiology includes a variety of central

nervous system, cardiovascular, otologic, and sensory causes. One of the most

common causes is benign positional vertigo, a peripheral vestibular

dysfunction. Although benign positional vertigo and many other causes are not

life threatening, dizziness from any cause can negatively affect the client's

life and cause injury. Since the cause of dizziness may be difficult to

diagnose, nursing management should focus on the impact of dizziness. Treatment

strategies should include frequent monitoring to improve overall health or to

deal with other conditions that may contribute to dizziness, safety measures to

prevent falls, patient education about antivertiginous medications, and

referral for vestibular rehabilitation. The advanced practice nurse (APN) plays

a significant role in the assessment of dizziness and the reduction of its

impact on the elderly client.

Case Study

Mrs. Smith is a 72-year-old woman residing

in an assisted living facility who complains of intermittent, daily episodes of

dizziness, usually while arising from bed. The episodes last several hours and

diminish in the early afternoon. She notes that the room spins and the feeling

is exacerbated by turning her head. Past medical history is significant for

myocardial infarction, mild heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and

hypothyroidism. Medications include atenolol 100 mg daily, verapamil 180 mg

daily, furosemide 20 mg daily, levothyroxine 0.1 mg daily, coumadin 5 mg daily,

and docusate 100 mg daily. She told her doctor about the dizziness, and was

prescribed meclizine 25 mg 3 times a day as needed, with only minor relief.

Mrs. Smith takes her meals in the dining room but often skips breakfast for

fear of falling on her way. She is worried about going to her niece's home for

a family party next week.

Introduction

Dizziness is a common symptom in people of

all ages, particularly the older adult. Dizziness is a generic term used to describe

a variety of experiences including giddiness, lightheadedness, faintness,

vertigo, fogginess, imbalance, unsteadiness, and ataxia. The etiology of a

person's complaint of dizziness is often difficult to identify. Origins include

problems of the inner ear and vestibular branch of the eighth cranial nerve,

cerebrovascular insufficiency and other problems of the central nervous system,

cardiovascular dysfunction, metabolic disorders, sensory deficits, and

emotional disorders (Table 1). A combination of causes occurs in many cases.

Older adults may accept dizziness as a symptom of aging without

seeking treatment. Others may become alarmed, associating dizziness with

life-threatening stroke or cardiovascular disease. Despite the etiology,

however, dizziness represents a significant hardship for many older adults.

Despite appropriate medical work up and interventions, the person's life might

continue to be greatly affected by dizziness. In many cases, the diagnosis is

not identified, or dizziness persists despite diagnosis and treatment. Quality

of life may be impaired, and falls and other injuries may result.

The APN can play an instrumental role in the management of

dizziness. The APN can help the person adapt to dizziness, ensure safety, and

even help alleviate the symptoms of dizziness. While the medical team of

specialists will focus on differentiating the underlying cause, the APN can

take a more patient-centered and holistic approach.

Scope of the Problem

Studies have shown that approximately one

quarter to one third of elderly in the community are dizzy.[1,2] One study showed that 1 in 10

respondents suffered from current, handicapping dizziness.[3] Many patients report dizziness to their

primary care provider (PCP), and 5% to 10% of new primary care visits are for

dizziness.[4]

The differential diagnosis of dizziness often presents a dilemma

to the PCP. Most people presenting with dizziness will have a normal physical

examination despite significant, often life-altering and debilitating,

symptoms. Laboratory testing and imaging studies usually prove worthless in

determining the diagnosis of dizziness.[5] The PCP often tries to narrow the

differential diagnosis by symptomatology to determine the appropriate referral.

Patients are more likely to be referred to a specialist if symptoms last 1 year

or longer, there is more than 1 visit to the PCP for dizziness, and there are

additional symptoms pointing to a cardiac; neurologic; or ear, nose, or throat

disorder.[6] Some researchers have set out to show that patients with

dizziness are underreferred[6] and that most cases of unexplained dizziness can be

diagnosed if work up is sufficiently extensive.[7,8] In fact, numerous studies have been done

to find out the diagnostic breakdown of dizziness in the elderly and to

determine predictors of certain causes that might assist in better evaluation

and referral criteria.[7-10] However, little outcome research has

been done to show improved quality of life or decreased morbidity and mortality

with aggressive evaluation and treatment for the vast differential of

dizziness.

Work by Tinetti and colleagues[11] takes a different approach to dizziness.

They have proposed that dizziness should be treated as a geriatric syndrome

rather than a symptom of an underlying disorder. They found that chronic

dizziness was not associated with increased mortality or hospitalizations.[11] They did find that dizziness was

associated with worsening of some quality-of-life indicators, as have other

studies,[2] as well as with risk of falling and depression. Falls or

fear of falling may be the greatest threat with dizziness. Burker and

colleagues[12] found that 47% of the elderly who are dizzy have a fear of

falling, as opposed to 3% of controls. Von Renteln-Kruse and colleagues[13] reported that elderly patients with

dizziness were 10 times more likely to report falls than those without

dizziness. Tinetti and colleagues[1] suggested that impairment reduction strategies might prove

more effective in reducing the disability of dizziness than focusing on

identifying and treating particular causes.

Screening and Assessment

Screening

Psychogenic dizziness is often listed as

an etiology of the complaint of dizziness. This seems to be a diagnosis of

exclusion when no other etiology can be found and the patient suffers from

anxiety, depression, or some other emotional malady. Many studies have shown a

correlation of dizziness to anxiety and depression, but have not proven a cause

and effect relationship.[2,14] Dizziness should be regarded as a

significant symptom with important impact on an elderly individual's well

being, and, therefore, all elderly people should be regularly screened for the

symptom of dizziness, especially those who also have anxiety and depression.

Likewise, a person who has complained of dizziness should also be screened for

emotional effects, including anxiety and depression.

General History

The approach to the patient with dizziness

should begin with an assessment of the complaint. Many patients will have

complained to their PCP of dizziness in the past. They may have seen

specialists, had diagnostic testing, and been told that it was nothing serious.

Antivertiginous medication such as meclizine may have been prescribed but may

not have worked, or the patient might have believed it wasn't worth taking.

This scenario is not a reason to stop the data gathering about

dizziness; rather, it is the perfect opportunity to explore the impact of

dizziness on the patient's life. Standard assessment parameters should be

explored, such as type of sensation experienced, frequency, duration,

intensity, precipitating and alleviating factors, and associated symptoms.

History findings may point to the etiology of dizziness, but, more importantly,

show areas for further evaluation, the impact of dizziness on the person, and

areas for intervention.

A number of patients have more than 1 sensation of dizziness.[1] A spinning sensation without

lightheadedness is more likely related to benign positional vertigo.[14] Syncope is often associated with

cardiovascular disorder.[9,10] Many patients -- but not all -- with

benign positional vertigo will report dizziness precipitated by position

change.[15]

Associated symptoms may be subtle and not previously reported by

the patient. Therefore, review of systems should be broad and include questions

about such things as general health, headache, visual or hearing problems,

tinnitus, signs of peripheral neuropathy, arthritis, neck pain, shortness of

breath and hyperventilation, palpitations, and nausea and vomiting.

Medication History

The patient's current and recent

medications should be evaluated. Use of aminoglycoside antibiotics may cause

ototoxicity, as can the loop diuretic ethacrynic acid. Use of any diuretics may

be associated with volume depletion, leading to lightheadedness.

Antihypertensives and vasodilators may cause postural lightheadedness.[16] Antihistamines, anticholinergic agents,

antidepressants, antianxiety agents, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and

just about any drug that works through the central nervous system may cause

dizziness in some people. A study of hospitalized patients ages 75 years and

older found that neuroleptics, antidepressants, hypnotics/sedatives, and

combinations of drugs with hypotensive effects were prescribed more frequently

in patients who reported dizziness.[13]

Some research has focused on the number of medications taken by

the elderly as being a factor in dizziness and falls. However, Hendrich and

colleagues[17] found that the presence of medication side effects was a

better predictor of falls than the medications themselves. Therefore,

medication history should include questioning about potential medication side

effects such as sedation, impaired balance, and dizziness.

Additionally, medications used to reduce dizziness should be

reviewed. Although meclizine and a few other antivertiginous agents are

approved for the treatment of vestibular-related dizziness, they may actually

cause or exacerbate dizziness. Paradoxic effects such as restlessness,

irritability, insomnia, euphoria, auditory and visual hallucinations, and

diplopia may occur in the elderly.[18] Antivertiginous medications are more effective for motion

sickness and acute labyrinthitis rather than benign positional vertigo and

other causes.[18,19] Therefore, if positive results are not

seen, these agents should be discontinued.

General Physical Examination

Physical examination should follow

history. If a thorough neurologic exam was done and no focal deficits were

documented, then it need not be repeated. However, there are several areas on

which the APN should focus. If the history reveals possible sensory deficits,

then vision, hearing, proprioception, light touch, and vibratory sensation

should be evaluated thoroughly. Dysequilibrium or other sensations of dizziness

may arise from multiple sensory deficits. Otoscopic assessment of the ears

should be conducted to screen for impacted cerumen or infection, which may

contribute to dizziness. A cardiovascular exam should include assessment for

vital signs, orthostatic blood pressure changes, carotid bruits, and

auscultation of the heart for rate, rhythm, and murmur. A new arrhythmia or

valvular dysfunction may contribute to dizziness.

Orthostatic changes. Physical assessment of the dizzy patient

should also focus on postural blood pressure changes. Orthostatic hypotension

occurs more commonly in the elderly and may be related to such conditions as

cardiovascular disorders, Parkinson's disease, or medication side effects.

Results of studies on the relationship between postural hypotension and

dizziness have varied based on varying parameters used to define orthostatic

changes.[1,20] Orthostatic hypotension is frequently defined as a drop in

systolic blood pressure of 20 mm on position change from supine to standing;

however, many studies have found more modest changes that relate to dizziness.

Hillen and colleagues[21] found that systolic decrease of 15 mm Hg and diastolic

decrease of 5 mm Hg related to dizziness. Tinetti and colleagues[1] found a relation only between mean blood

pressure change and dizziness, possibly because mean blood pressure correlates

better with cerebral perfusion.

In any case, blood pressure and pulse responses to position change

should be assessed immediately and at 2 minutes to screen for orthostatic

hypotension that may be related to dizziness. The patient should also be

observed for clinical signs and symptoms such as nausea, pallor, dizziness,

visual dimming, and decreased consciousness in assessing orthostasis.[22]

Dix-Hallpike maneuver. Provocation tests for dizziness often

identify dizziness of a vestibular nature and thus rule out the need for a more

thorough cardiac work up. The Dix-Hallpike maneuver (also called the Nylen

maneuver, Barany maneuver, or drop test) should be performed on all patients

complaining of dizziness. It can be done on an examination table or in the

patient's bed, provided there is room for the patient's head to hang over the

edge of the bed. The procedure should be explained to the patient thoroughly

prior to the maneuver (Table 2).

The Dix-Hallpike is diagnostic for benign positional vertigo when

dizziness is reproduced by this maneuver with nystagmus to 1 side that occurs

after a 4-5 second latent period. If nystagmus occurs immediately upon this

maneuver, lasts more than 30 seconds, is exclusively vertical, or is

nonfatiguable with repeated maneuvers, then a serious central nervous system

lesion may be present.[18,23]

In a study[15] of 191 patients referred to a neurology clinic with a

variety of diagnoses and complaints such as unusual sensations of dizziness,

neck pain, and headache, 36 were identified with benign positional vertigo. The

Dix-Hallpike had not been performed on any of these patients prior to referral.

The authors concluded that the Dix-Hallpike is mandatory for all patients

complaining of dizziness or vertigo. Had it been performed in the primary care

or long-term care setting, unnecessary work up and referral might have been

avoided.

Management

Treatment of Etiologic Factors

Obviously, etiologic factors for dizziness

should be treated whenever possible. The APN can ensure that identified

cardiovascular disorders are monitored and controlled adequately. The APN should

facilitate additional testing such as electrocardiogram (EKG) and

echocardiogram, and refer to the cardiologist if the patient becomes

symptomatic, has difficulty adhering to the medication regime, or shows signs

of decompensation such as heart failure. For sensory deficits related to

dizziness, the APN can help the patient obtain a hearing aid, visual

correction, and ambulatory aids. The APN can treat impacted cerumen and make

referral for additional ear problems. The APN should make recommendations for

adjustments to the medication regime if dizziness is thought to be a side

effect of 1 or a group of medications.

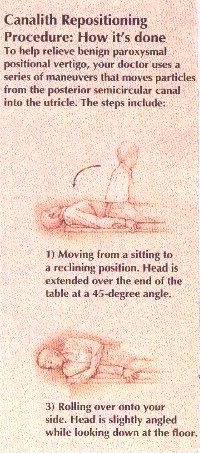

Vestibular Rehabilitation

Vestibular rehabilitation, also known as

vestibular exercises, canalith repositioning maneuver, or the Epley maneuver,

is the one definitive treatment for vestibular causes of dizziness. It can

greatly reduce the symptom of dizziness, but unfortunately is not widely used

in many settings. It may be done by the clinician immediately following a

positive Dix-Hallpike maneuver[23] and often produces a dramatic decrease in dizziness.

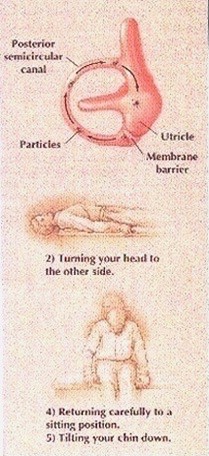

Because benign positional vertigo results from the free movement

of dislodged particulate debris into the posterior semicircular canal,

vestibular rehabilitation acts to reposition the loose particles from the

posterior semicircular canal into the utricle. This is accomplished by

maneuvering the patient's head into certain positions. For patients

with central causes of dizziness, vestibular rehabilitation may also include

gait training and strengthening of other sensory functions to compensate for

vestibular dysfunction.[16] A physical therapist may be consulted in any case.

Vestibular exercises may be performed several times by the therapist, then

taught to the patient to perform at home. Antivertiginous and central nervous

system medications should be avoided during therapy because the sensation of

dizziness is required for effective compensation.[18]

Efficacy of vestibular rehabilitation was retrospectively studied[24] in 37 patients with both peripheral and

central vestibular etiologies of dizziness by comparing dizziness handicap

inventory scores pretreatment and posttreatment within 1 year of vestibular

rehabilitation. A significant improvement in test scores was found

posttreatment. There was no significant difference in improvement between

patients who performed home exercises for at least 1 month and those who

participated in initial therapy only. Gordon and colleagues[15] found complete resolution of dizziness

in 83% of patients diagnosed with benign positional vertigo following 1

physical therapy session. The APN should use this knowledge to facilitate

referral of the patient with chronic dizziness to a physical therapist who

provides vestibular rehabilitation. This is an option that may not have been

considered by the PCP or specialist evaluating the patient in the past.

Antivertiginous Medications

Antivertiginous medications, particularly

meclizine, are prescribed widely for all ages of people who are dizzy. These

agents, however, are most effective for motion sickness and only possibly

effective for vertigo caused by vestibular disorders. These drugs may have

central nervous system depressant effects or paradoxic effects in the elderly.

They have anticholinergic effects so should be avoided with narrow angle

glaucoma, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and gastric and genitourinary outlet

obstruction. Additional anticholinergic side effects, which may be additive

with other anticholinergics, may include xerostomia, blurred vision,

constipation, urinary retention, and mental status changes.

Despite the precautions, meclizine 12.5 mg to 25 mg may be used 2

to 3 times daily to control or prevent dizziness. It works by decreasing

labyrinth excitability and conduction in the vestibular-cerebellar pathways.

Onset of action is 20 minutes to 60 minutes, so meclizine may do little to

treat a vertiginous attack already in progress. Elderly patients should be

cautioned to avoid activities that require mental alertness, such as driving,

until the effects of the medication are fully revealed.

Diphenidol is another antivertiginous and antiemetic medication

that is sometimes used for vertigo associated with nausea and vomiting. It is

not a first-line agent because of its propensity for central nervous system

side effects such as mental status changes, hallucinations, disorientation, and

confusion. Dimenhydrinate is an antihistamine used for motion sickness. It may

cause central nervous system side effects and photosensitivity.

The APN should take an active role in educating patients about

these drugs, their side effects, proper use, and limitations. Care should be

taken to avoid interactions of other drugs with anticholinergic and central

nervous system effects. The APN can monitor drug effectiveness with the patient

and should recommend discontinuing the drug if significant side effects occur

or no benefit is seen.

Ensuring Safety

Safety is a primary concern for the

elderly patient who is dizzy, both to prevent injury and to prevent inactivity

and withdrawal due to fear of falling. There are a number of ways the APN can

intervene to ensure the elderly patient's safety. First, the patient's

immediate environment should be safety-proofed to prevent injury if the patient

becomes dizzy and unsteady. The patient should be encouraged to wear properly

fitting nonslip footwear. Furniture should be removed that has sharp edges or

that may be an obstruction. Throw rugs should be removed, lighting should be

good, and steps should be fully visible with handrails on 2 sides. The patient

should be taught how to arise slowly and avoid sudden position changes if

postural or position changes aggravate dizziness. T'ai Chi may be helpful for

improving balance in people with dizziness and dysequilibrium. Research has

shown significant improvement in people with mild balance disorders.[25]

The topic of driving should be discussed with the dizzy patient.

Although many elderly patients depend on driving for daily functioning, dizziness

poses a potentially lethal threat. In 1 study,[26] few dizzy subjects had been warned by

their doctors not to drive, and 52% said that if they were warned to stop

driving, they would not. Therefore, the topic needs to be approached

sensitively, in an effort to help the patient avoid dependence on driving while

dizzy. Plans should be made for alternate transportation if the patient is

dizzy, and an emergency plan can be made to stop the car in a safe place if

dizziness ensues while driving.

Summary

The APN is in a unique position to

intervene with the elderly client who is dizzy, no matter what the cause. While

the medical work up is progressing, as well as following the diagnosis, the APN

can address the impact of dizziness on the patient. The APN should determine if

a thorough neurologic and cardiovascular examination has been performed. Unless

focal neurologic deficits, severe headache, and vertical nystagmus are present,

neuroimaging is not necessary. The Dix-Hallpike maneuver should be performed on

all dizzy patients to rule out a benign peripheral vestibular etiology for the

dizziness. A positive test indicates the need for vestibular rehabilitation.

The APN should facilitate this referral to a physical therapist and involve the

patient's family and other caregivers to help address issues of fall

prevention, driving safety, and careful use of antivertiginous medications.

Case Study -- Conclusion

The medical record for Mrs. Smith

indicated a normal neurologic examination with negative Romberg test and intact

proprioception, reflexes, and light touch sensation, but the Dix-Hallpike

maneuver had not been performed. Cardiac and audiologic evaluations were

normal. The APN repeated an ear exam, which revealed no abnormalities. The APN

also evaluated for postural hypotension, which was absent, obtained an EKG that

revealed normal sinus rhythm, and performed a Dix-Hallpike maneuver. The

Dix-Hallpike revealed positive horizontal nystagmus toward the left that

disappeared when tried again. This finding with history of intermittent

positional vertigo confirmed a diagnosis of benign positional vertigo. The APN

recommended that Mrs. Smith's meclizine be discontinued since it was not

effective. A referral was made for treatment by a physical therapist for

vestibular rehabilitation. Following 2 treatments, Mrs. Smith's dizziness was

significantly better and she began going to the dining room every morning. The

physical therapist suggested that a cane could be obtained if Mrs. Smith

desired until she became completely steady. Mrs. Smith refused. The APN asked

the staff to make sure that Mrs. Smith wear appropriate footwear at all times,

and to keep her room free from clutter. The APN continued to monitor Mrs.

Smith's cardiac status and coagulation profile and reinforced patient and staff

education to prevent bleeding with anticoagulant use.

Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of Dizziness

|

Character of Dizziness |

Mechanism |

Examples |

|

Lightheadedness, faintness, presyncope |

Vaso-vagal mediated |

Carotid sinus hypersensitivity |

|

Neuromediated |

Volume depletion |

|

|

Autonomic neuropathy of diabetes |

||

|

Severe anemia |

||

|

Aortic stenosis |

||

|

Drugs |

||

|

Metabolic disturbance |

Hypoglycemia |

|

|

Hypoxia |

||

|

Vertigo |

Peripheral vestibular |

Benign positional vertigo |

|

Labyrinthitis |

||

|

Meniere's disease |

||

|

Ototoxic drugs |

||

|

Acoustic neuroma |

||

|

Central vestibular |

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency |

|

|

Multiple sclerosis |

||

|

Drugs in excess |

||

|

Ataxia, dysequilibrium |

Multiple sensory deficits |

Diabetes mellitus |

|

Impaired vision |

||

|

Motor problems |

||

|

Cerebellar disease |

Cerebellar degeneration |

|

|

Cerebellar hemorrhage |

||

|

Ill-defined dizziness, anxiety,

fogginess, malaise |

Psychiatric illness |

Anxiety |

|

Depression |

||

|

Psychosis |

.

Table 2. The Dix-Hallpike Test

|

1. |

With patient sitting on the exam table,

maximally extend the neck (to 45 degrees) and turn the head 45 degrees to one

side. |

|

2. |

Support the patient's upper body and ask

the patient to keep eyes open and look at your forehead. |

|

3. |

Suddenly drop the patient backward with

the head over the edge of the table. |

|

4. |

Observe the patient's eyes for at least

15 seconds for the presence of nystagmus. |

|

5. |

Repeat with the head rotated in the

opposite direction. The side with the down ear that produces nystagmus is the

side with the vestibular lesion. |

References

- Tinetti

ME, Williams CS, Gill TM. Dizziness among older adults: a possible

geriatric syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:337-344.

- Grimby

A, Rosenhall U. Health-related quality of life and dizziness in old age.

Gerontology. 1995;41:286-298.

- Yardley

L, Burgneay J, Andersson G, Owen N, Nazareth I, Luxon L. Feasibility and

effectiveness of providing vestibular rehabilitation for dizzy patients in

the community. Clin Otolaryngol. 1998;23:442-448.

- Healthtouch

Online. General information on dizziness. Available at: http://www.healthtouch.com/bin/EContent_HT/hdShowLfts.asp?lftname=NINDS014&cid=HTHLTH.

Accessed April 10, 2001.

- Colledge

NR, Barr-Hamilton RM, Lewis SJ, Sellar RJ, Wilson JA. Evaluation of

investigations to diagnose the cause of dizziness in elderly people: a

community based controlled study. BMJ. 1996;313:788-792.

- Bird JC,

Beynon GJ, Prevost AT, Baguley DM. An analysis of referral patterns for

dizziness in the primary care setting. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1828-1832.

- Bath AP,

Walsh RM, Ranalli P, et al. Experience from a multidisciplinary

"dizzy" clinic. Am J Otol. 2000;21:92-97.

- O'Mahony

D, Foote C. Prospective evaluation of unexplained syncope, dizziness, and

falls among community-dwelling elderly adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med

Sci. 1998;53;M435-M440.

- Lawson

J, Fitzgerald J, Birchall J, Aldren CP, Kenny RA. Diagnosis of geriatric

patients with severe dizziness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:12-17.

- Allcock

LM, O'Shea D. Diagnostic yield and development of a neurocardiovascular

investigation unit for older adults in a district hospital. J Gerontol A

Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M458-M462.

- Tinetti

ME, Williams CS, Gill TM. Health, functional, and psychological outcomes

among older persons with chronic dizziness. J Am Geriatr Soc.

2000;48:417-421.

- Burker

EJ, Wong H, Sloane PD, Mattingly D, Preisser J, Mitchell CM. Predictors of

fear of falling in dizzy and nondizzy elderly. Psychol Aging.

1995;10:104-110.

- Von

Renteln-Kruse W, Micol W, Oster P, Schlierf G. Prescription drugs,

dizziness and accidental falls in hospital patients over 75 years of age.

Z Gerontol Geriatr. 1998;31:286-289.

- Oghalai

JS, Manolidis S, Barth JL, Stewart MG, Jenkins HA. Unrecognized benign

positional vertigo in elderly patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

2000;122:630-634.

- Gordon

CR, Aur O, Furas R, Kott E, Gadoth N. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of benign

positional vertigo. Harefuah. 2000;138:1024-1027, 1087.

- Goroll

AH, May LA, Mulley AG. Primary Care Medicine: Office Evaluation and

Management of the Adult Patient. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott,

Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

- Hendrich

A, Nyhuis A, Kippenbrock T, Soja ME. Hospital falls: development of a

predictive model for clinical practice. Appl Nurs Res. 1995;8:129-139.

- Cohen H,

Mesad SM. Dizziness, vertigo, and ataxia. In: Primary Care.

Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

- Pepper

RM. Dizziness. In: Rakel RE, ed. Saunders Manual of Medical

Practice. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 1996.

- Tilvis

RJ, Hakula SM, Valvanne J, Erkinjuntti T. Postural hypotension and

dizziness in a general aged population: a four-year follow-up of the

Helsinki Aging Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:809-814.

- Hillen

ME, Wagner ML, Sage JI. "Subclinical" orthostatic hypotension is

associated with dizziness in elderly patients with Parkinson disease. Arch

Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:710-712.

- Winslow

EH, Lane LE, Woods RJ. Dangling: a review of relevant physiology,

research, and practice. Heart Lung. 1995;24:263-272.

- Orient

JM. Sapira's Art & Science of Bedside Diagnosis. 2nd

ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

- Cowand

JL, Wrisley DM, Walker M, Stasnick B, Jacobson JT. Efficacy of vestibular

rehabilitation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:49-54.

- Hain TC,

Fuler L, Weil L, Kotsias J. Effects of T'ai Chi on balance. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:1191-1195.

- Sindwani

R, Parnes LS, Goebel JA, Cass SP. Approach to the vestibular patient and

driving: a patient perspective. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

1999;121:13-17.

Edward E.

Rylander, M.D.

Diplomat American

Board of Family Practice.

Diplomat American

Board of Palliative Medicine.